Журнальный клуб Интелрос » Joint Force Quarterly » №84, 2016

Active and Reserve Servicemembers spend in excess of 3 million hours (roughly 342 years) annually preparing, rating, reviewing, and socializing military professional evaluations up and down the chain of command before submission to their respective Services.1 With almost 1.4 million Active-duty and 800,000 National Guard and Reserve personnel, the U.S. military stands as one of the largest assessment organizations in the world.2 Yet each Service has its own stovepiped assessment system that essentially evaluates the same thing: identifying those most qualified for advancement and assignment to positions of increased responsibility. These systems appear to support this goal within their respective Services well enough, despite occasional evaluation overhauls.3Nevertheless, these disparate and divergent evaluation systems burden joint operations, distract from larger Department of Defense (DOD) personnel initiatives, degrade the joint force’s ability to achieve national military objectives, and inefficiently expend limited resources. Furthermore, the highest military positions remain at the joint, interagency, and secretariat levels.

USS Nimitz conducts Tailored Ship’s Training Availability and Final Evaluation Problem, which evaluates crew on performance during training drills and real-world scenarios, Pacific Ocean, November 2016 (U.S. Navy/Siobhana R. McEwen)

These critiques occur not only at evaluation time when raters and reporting seniors scramble to comprehend, fill out, and complete evaluations for their ratees per their respective Services’ requirements and guidelines, but also when DOD and the joint force need to identify skilled and competent Servicemembers for special programs and operational assignments, certify joint credit and qualifications, or fulfill and track DOD-wide personnel initiatives.4Recently, DOD has faced scathing criticism for its inability to hold the Services accountable during the performance evaluation process or monitor professionalism issues linked to ethics, gender issues, and command climate.5 For their part, the Services have employed their evaluation systems to monitor some of these issues as well as others that may exist within their evaluation processes. For instance, the Marine Corps commissioned multiple studies over the last decade to assess the extent to which biases exist within officer evaluations based on occupation, race, gender, commissioning source, age at commissioning, marital status, type of duty (combat vs. noncombat), and educational achievement.6 While these individual efforts are helpful, they could be better coordinated among the Services and joint force to arrest what are essentially shared, cross-Service personnel challenges.

Incongruent evaluation systems also degrade the ability of the joint force to face stated national military objectives more effectively. The Capstone Concept of Joint Operations stresses that “the strength of any Joint Force has always been the combining of unique Service capabilities into a coherent operational whole.”7 Moreover, the 2015 National Military Strategy elaborates that the “Joint Force combines people, processes, and programs to execute globally integrated operations,” while “exploring how our [joint] personnel policies . . . must evolve to leverage 21st-century skills.”8 There is no reason why an evaluation system should not align with joint force leadership and operational doctrine. An integrated personnel evaluation system would be instrumental in achieving the goal for both the global integrated operations concept and national military objectives. Besides, enhanced jointness already exists within many military specialty communities that have similar performance measures, such as health care and medical services, special operations, chaplain corps, logistics, cyber, public affairs, electronic warfare, military police, intelligence, and engineering.

Finally, the comparative time expended by the combatant commanders (CCDRs) on fulfilling four different evaluation systems’ requirements is inherently inefficient and amounts to what economists equate to lost productivity. Meanwhile, the Services spend millions of dollars annually on the personnel, facilities, and support systems required to administer these systems, even though many of the Services’ core evaluation functions are shared and overlap. Combined, these diminish both short- and long-term efficiencies and resources. Regrettably, no comprehensive study has evaluated the U.S. military’s myriad of personnel evaluation systems as a whole, nor has a study assessed the lost productivity and resources consumed in maintaining these separate regimes. DOD would better serve the CCDRs and operational commitments by coupling its human capital with a simple, efficient, standardized, and joint evaluation system: the Joint Evaluation System (JVAL). JVAL offers DOD and the CCDRs a viable and valuable yardstick to measure personnel capabilities and capacities. But before highlighting possible constructs for JVAL or the methods in which it could be implemented, a broad look at the status quo of the four Service-centric evaluations is in order.

Status Quo of Service Evaluations

Across the Services, officers’ careers generally begin with a focus on entry-level technical, managerial, and tactical skills, which steadily evolve into more senior-level supervisory, operational, and strategic skills as they progress along the career continuum. The intent of the various Service-centric evaluation systems is to capture that progression. But the mechanisms used to accomplish that task could not be more dissimilar. Each Service’s evaluation system breaks away from the others in a variety of ways: the number of evaluations, scope, nomenclature, delivery, intent, language, content, format, length, and style, among others. Singling out the first five of these (number, scope, nomenclature, delivery, and intent) succinctly illustrates this point.

First, three of the Services (the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps) maintain a single, Service-related evaluation for officers and warrant officers (notwithstanding the Air Force) up to the O6 level.9 In contrast, the Army uses three different evaluations to track its officer career continuum: company grade (O1-O3, WO1-CW2), field grade (O4-O5, CW3-CW5), and strategic grade (O6).10 It is worth pointing out that the Marine Corps is the most inclusive of all the Services in number and scope since the same Performance Evaluation System (PES) form encompasses the ranks of E5 up to O6. Second, the nomenclature assigned by each Service is different: the Navy uses the Fitness Report (FITREP), Marine Corps the PES, Army the Officer Evaluation System (OES), and Air Force the Officer Performance Report (OPR). With regard to delivery, the Navy remains the only Service that does not have the capability for the evaluation form to be delivered in real time through a Web-based application and portal.11 Instead, Navy evaluation reviewing officials are required to mail their rated FITREPs to Navy Personnel Command. This can delay the completion of the evaluation process by up to a week or more.

Instructor administers OC spray during OC Spray Performance Evaluation Course, part of Non-Lethal Weapons Instructor Course, on Camp Hansen, Okinawa, Japan, August 2015 (U.S. Marine Corps/Thor Larson)

Finally, the intent with which the Services view their evaluation systems is markedly different. The 184-page Marines’ Performance Evaluation System manual, the shortest among the Services, notes that the PES “provides the primary means for evaluating a Marine’s performance to support the Commandant’s efforts to select the best qualified personnel for promotion, augmentation, retention, resident schooling, command, and duty assignments.”12 Meanwhile, the expansive 488-page Army Pamphlet 600–3, Commissioned Officer Professional Development and Career Management, which incorporates the OES, echoes its sister Service’s findings and further elaborates that evaluations can assist with functional description, elimination, reduction in force, and command and project manager designation.13 Additionally, the Army leverages its OES to encourage the “professional development of the officer corps through structured performance and developmental assessment and counseling,” as well as promoting the leadership and mentoring of officers in specific elements of the Army Leadership Doctrine.14 After considering just these five differences, it appears that there is no overlap or commonality among evaluations. On the contrary, there is. These differences, along with the others mentioned earlier, become less apparent once the overall format and flow of the evaluation forms are compared.

Are the Various Service Evaluations One and the Same? Each of the Services’ evaluations can essentially be broken down into four general sections: a standard identification section, a measurements and assessment section (with or without substantiating comments), a section for rating official or reviewing official commentary and ranking of the ratee, and, finally, a redress or adverse remarks section. These sections are important because they are directly applicable to the proposed JVAL constructs to be described later.

Standard Identification. All of the Services begin their evaluation form with the same boilerplate administrative section. This section generally includes the ratee’s name, social security number or DOD identification number, rank, period of evaluation, title, duty description, occupational designator, and unit assignment. Separately, the rater’s and reviewing officials’ relevant information is also included in this section.15 The two key takeaways from this section are that the ratee is immediately identified by overall functional capability or category in either operations, operations support, or sustainment, and the rater and reviewing official are identified.16

Measurement/Assessment. This is the second most important of the four sections since it rates ratees’ capabilities against their Service’s performance standards through a variety of metrics. The Services are split evenly in their approach to the metrics portion between either a binary yes or no (for the Army and Air Force) or an ascending scale (ranging from 1 to 5 for the Navy and from A to G for the Marines).17 The two most commonly shared traits for assessment among the Services are character and leadership. However, the actual count of trait-related performance metrics varies substantially from a high of 14 for the Marines’ PES to a low of 6 for the Air Force’s OPR.18 For some Services, the performance metrics do not align or are excluded entirely. For example, physical fitness standards are not explicitly listed in Air Force or Navy evaluations. Instead, they are filled in by the ratee and verified by the rater in other areas of the evaluation.

The same is true for supporting commentary. For the Marines and Army, each performance metric is tied to corroborating commentary. This is not the case for both the Air Force and Navy, which have separate areas for commentary that are detached from their performance metrics rankings.19 In either case, the commentary allows ratees the opportunity to describe and validate their performance in advantageous or disadvantageous terms (subject to any revisions by the raters or reviewing officials). More importantly, this language even can note the ratees’ rankings among a subsection of their peer group or among the entire peer group (otherwise known as a hard or soft breakout in the Navy’s FITREP). It should be of no surprise that the Services have neither performance metrics nor commentary explicitly designated on their evaluations for joint force or DOD-related initiatives, such as joint professional military education and sexual assault prevention.

Rating Official/Reviewing Official Remarks. This is the most important section of the evaluation process because it includes a ranking scheme and competitive promotion category for the ratee. For rankings, each Service allows the rating official to rank or score the ratee against a subsection of the ratee’s peer group or among the entire peer group. This is commonly referred to as stratification. The score presented to the ratee by the rater usually includes a cardinal number to denote the quantity of officers evaluated by the rater with a corresponding ordinal number for the ratee’s rank among his or her peers. The rater’s ranking profile (essentially the historical composite score of the rater’s previous rankings) plays an important role later in establishing and tracking the ratee’s relative score against those of the rater.

Rater profiles and scores remain a contentious issue among the Services because some raters’ profiles and scorings may be immature, skewed, or, in the worst case, trend upward (known as inflation). Indeed, scoring inflation has been a systemic problem across all the Services. The Army has routinely revised its evaluations to tamp down on inflation, and the Marines commissioned studies to assess the extent to which grade inflation persists in the PES.20 To combat ranking inflation, the Services have increased training for raters and instituted mandatory ceilings and floors for scoring and rankings. This has resulted in a significant reduction in overall inflation; however, the problem still exists and is actively monitored by the Services.

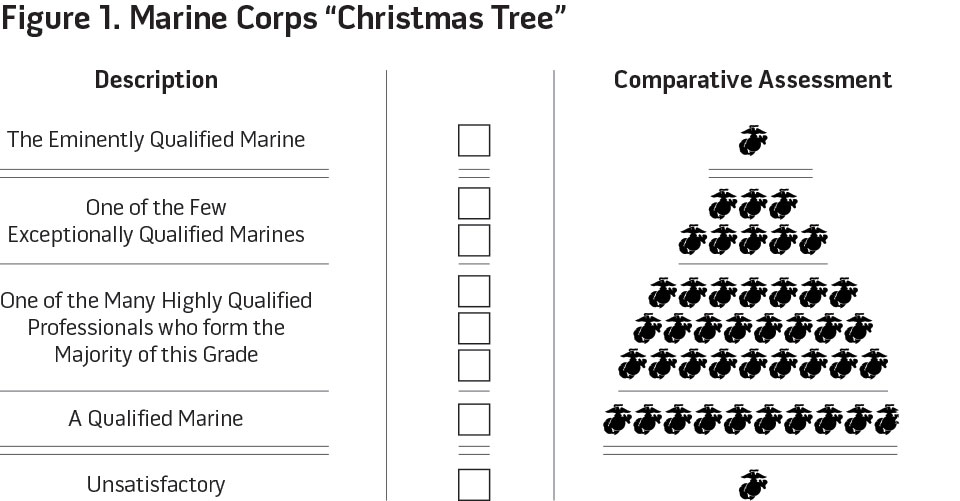

Finally, the Services have competitive promotion groupings under which the rater classifies the ratee. The Army’s previous OER, DA Form 67-9, allowed the senior rater to mark the ratee as Above Center of Mass, Center of Mass, Below Center of Mass Retain, and Below Center of Mass Do Not Retain. In the PES, the reviewing official marks the ratee for comparative assessment using the Marines’ iconographic “Christmas Tree” with the Eminently Qualified Marine at the top of the “tree” to Unsatisfactory at the bottom (see figure 1). The Navy has five promotion categories ranging from Significant Problems to Early Promote, whereas the Air Force has three: Definitely Promote, Promote, and Do Not Promote.21

Redress/Adverse Remarks. The final section is reserved for an acknowledgment statement by the rater and provides the opportunity for the ratee to challenge or appeal any portion of the evaluation with supporting documentation. Unless additional documentation is submitted, this is the shortest section for each of the Services’ evaluations. It is worth noting that the Services unanimously point out that the evaluation forms are not to be used as a counseling tool under any circumstances.

Evaluations Remain a Pyramidal Scheme. The purpose of highlighting these four sections is to point out the significant commonalities among the Services’ evaluation systems. Evaluations remain an understated and underappreciated, if not uniformly shared, responsibility among the Services. Regardless of their differences, these systems all seek the same goal: to identify those officers most qualified for advancement and assignment to positions of increased responsibility. Army Pamphlet 600–3, Commissioned Officer Professional Development and Career Management, is spot on when it describes the officer evaluation structure as “pyramidal” with an “apex” that contains “very few senior grades in relation to the wider base.”22 Furthermore, Pamphlet 600–3 notes that advancement within this pyramid to increasingly responsible positions is based on “relative measures of performance and potential” and evaluations are the “mechanisms to judge the value of an individual’s performance and potential.”23 This is as true for the Army as it is for the joint force. As such, all the Service-centric officer evaluations are prime for rollup into JVAL.

JVAL Constructs

Unifying four dissimilar evaluation systems is no small task. Ostensibly, it is unlikely that the Services will surrender their traditional roles and responsibilities in the personnel domain. However, JVAL is not mutually exclusive. The beauty of the JVAL construct is that it can be incorporated piecemeal or as a whole by the Services and joint force. JVAL’s constructs allow the Services to tier or scale their respective evaluation systems through three main approaches: joint-centric, Service-centric, or hybrid.

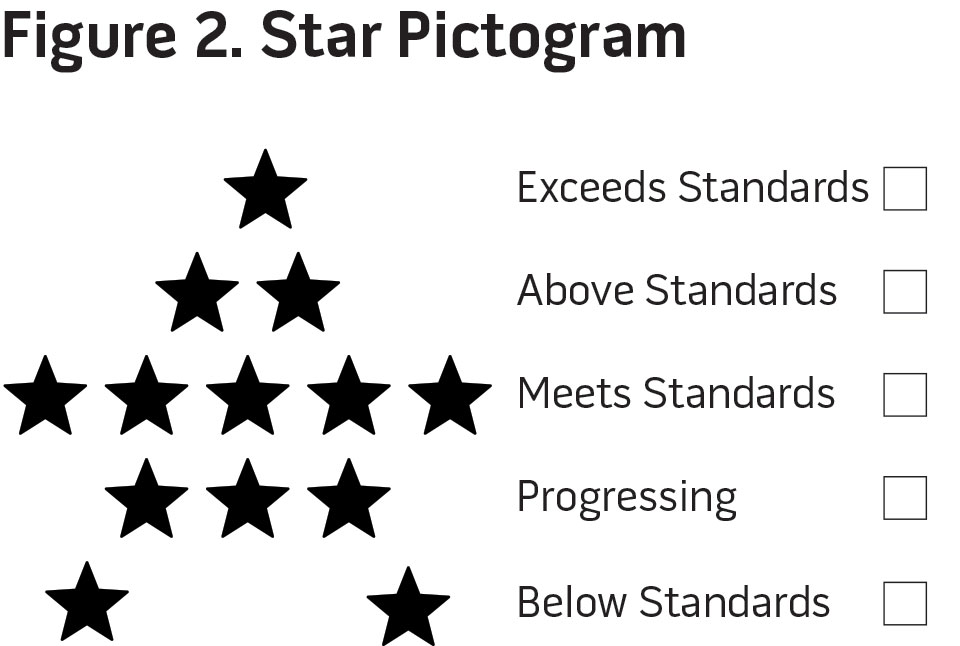

Joint-Centric. This is the most dynamic and efficient approach to JVAL, as it rolls all the Services’ evaluation systems into one unified evaluation system. The format and template for the joint-centric construct would align with the four de facto sections noted earlier: an identification section, a performance metric section matching substantiating commentary, a rater assessment section with ranking and promotion category, and a redress or adverse remarks section. Out of these four sections, selecting the performance metrics from the four current evaluations systems likely will present the greatest challenge to finalizing the joint-centric template. Likewise, the distinctive Service formats, styles, and delivery methods will need to be addressed. However, these can be properly vetted during the implementation stage to be described later. One idea for the comparative assessment portion could incorporate a pictogram of a star, similar to the Marines’ “Christmas Tree,” with five competitive categories from highest to low: Exceeds Standards, Above Standards, Meets Standards, Progressing, and Below Standards (see figure 2).

The two most important features that the joint-centric construct offers are the method of delivery and the short- and long-term gains in efficiencies and resources associated with implementing one evaluation system. The joint-centric construct envisions delivery through a secure, Web-enabled portal and application. This capability would not only allow JVAL to be readily completed, socialized, reviewed, and submitted, but also permit DOD, the joint force, and the Services to readily access, search, and analyze their personnel’s performance and capabilities. At the same time, DOD would be able to directly propagate and measure DOD-wide initiatives and policies. JVAL might even be used to create a repository of profiles to track skill sets, personnel progression, and assignments by the entire joint force and Services. JVAL could become a clearinghouse for personnel evaluations in the same way Defense Finance and Accounting Services has with military pay and finances.

Finally, by combining the four Services’ evaluation-related personnel, facilities, and support systems, DOD would realize millions of dollars in costs savings annually, take back lost productivity, and increase efficiencies. Right-sizing personnel, facilities, and support systems is relatively easy to quantify in budget terms. However, efficiencies are tricky to ascertain since many are intangible or have not been properly researched. For example, under one evaluation system, a Servicemember’s separation or retirement into a post-military career would be less intimidating and more transparent if a standardized performance measure existed for potential employers and the transitioning veteran to gauge their skills.24 Second, inter-Service transfers, augmentation by Reserve and Guard personnel, and joint task force mobilizations would be more seamless if a shared evaluation system existed by which to measure personnel capabilities. Finally, it would alleviate the need, however minor, for Service-specific raters and reviewers within organizations.

Service-Centric. Under the Service-centric construct, the Services would retain full control of their current evaluation systems. However, the Services’ evaluation systems and information would be fed directly into the larger joint force– and DOD-supported JVAL. The main difference would be that there would be two parallel systems working in tandem: the traditional Service evaluation system and the new JVAL. The critical component for this approach would be that the actual inputs selected for inclusion into JVAL from the Services’ systems would need to be vetted and scaled by all parties in order to populate the agreed-upon JVAL template. In this case, JVAL would resemble the template and delivery envisioned for the joint-centric construct, but with an additional bureaucratic and operational layer at the joint force and DOD level to maintain the JVAL evaluation process. As a result, the Service-centric construct would be the least dynamic and efficient approach to JVAL.

Hybrid. As its name implies, the hybrid construct merges selected portions from both the joint- and Service-centric models. These portions could be combined in any number of ways. One possible combination might divide evaluations by rank so that junior and warrant officer evaluations (WOs/O1-O4) would fall under the Service-centric approach and senior officer evaluations (O5-O6) under the joint-centric one. This combination would sync well with the existing officer career progression that places senior officers in more joint roles and responsibilities over time. Thus, efficiencies and cost savings could be divided between the Services, the joint force, and DOD. Finally, the hybrid construct would be an ideal intermediary point between both JVAL extremes (joint and Service) or act as an incremental stopping point before fully adopting the joint-centric approach. In any event, these three proposed JVAL constructs will achieve a more holistic and unified approach to officer evaluations in lieu of the status quo. Unfortunately, there is no JVAL-like program under consideration.

Pacific Fleet Master Chief inspects chief selectees at group PT session on Naval Air Facility Atsugi, Atsugi, Japan, August 2011 (U.S. Navy/Justin Smelley)

Current Reforms Omit JVAL

DOD unveiled one of the most significant personnel initiatives in a generation, Force of the Future (FotF), in 2015.25Although FotF unleashed a cascade of Service-related personnel reforms from retirement to promotion schedules to diversity alongside a host of corresponding Service-specific programs, such as the Department of the Navy’s Talent Management, FotF omitted evaluation reform.26 This is an unfortunate omission among the myriad of novel proposals encapsulated in FotF because its launch provided an opportune moment to address the disjointed and disparate Service-centric evaluation systems.27 Besides, DOD began phasing in its new civilian employee performance and appraisal program around the rollout of FotF. New Beginnings started April 1, 2016. The first phase incorporated about 15,000 employees at a handful of locations, including the National Capital Region, with additional phases to integrate most of the remaining 750,000 DOD civilian employees by 2018.28 Taking a page from FotF and New Beginnings, DOD could pursue a similar top-down approach to implement JVAL. However, this approach would likely require congressional legislative changes to Title 10, reinterpretation of existing Title 10 authorities, or Presidential directives that challenge the Service’s hegemony over personnel evaluations.

Haven’t the Services Always Rated Themselves? The military Service secretaries traditionally have been responsible for “administrating” their Service personnel under Title 10, and, reciprocally, the Services have codified this within their respective regulations.29 For example, the Department of the Navy’s General Regulations state explicitly that the “Chief of Naval Operations and the Commandant of the Marine Corps shall be responsible for the maintenance and administration of the records and reports in their respective services.”30 On the other hand, Title 10 also grants the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness (USDP&R), per the Secretary of Defense, to prescribe in the “areas of military readiness, total force management, military and civilian personnel requirements, and National Guard and reserve components” with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs overseeing supervision of “Total Force manpower, personnel, and reserve affairs.”31 While there appears to be no previous challenge to these statutory delineations with regard to evaluation policies, any changes would certainly engender pushback from the Services.

Language could be inserted within the congressional National Defense Authorization Act to include JVAL or to reassign personnel roles and responsibilities in light of these possible statutory limitations. In the alternative, there are a variety of internal and external options for DOD to institute JVAL without resorting to seismic revisions in extant laws, such as inter-Service memorandums of agreement, Joint Chiefs of Staff instructions, and Office of the Secretary of Defense policy directives to expand FotF. Reinterpreting Title 10 authorities could be another option. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff does have broad Title 10 powers that include “formulating policies for concept development and experimentation for the joint employment of the armed forces.”32 As noted, it is unlikely that the Services will surrender their personnel systems so easily. This is precisely why DOD and the joint force need to incentivize the Services through the efficiencies, cost savings, and overall personnel readiness that JVAL offers.

JVAL Implementation. Once approved, the most realistic approach for implementing JVAL would be for DOD to identify the USDP&R with the overall responsibility and assign one of its principals or deputies to act as the executive agent.33 To carry out that responsibility, the executive agent would then establish three standing groups: the Executive Steering Group, Senior Advisory Group, and Joint Integrated Process Team. Consisting of Senior Executive Service civilians and senior flag officers, each group would have its own unique set of tasks and responsibilities in order to plan, support, collaborate, and implement JVAL in a time-phased approach. An initial pilot program would be recommended, and, if successful, would transition into a rollout period of 3 to 4 years. This rollout period would coincide with policy and regulation revisions, strategic communications, system development, realignment of infrastructure and facilities, right-sizing of personnel, transfer of previous evaluations, and deployment of mobile training demonstrations and teams. At that time, JVAL could be expanded to include general and flag officers as well as the enlisted ranks. This long and complex method is preferable for DOD because it allows the Services the opportunity to properly uncouple previous personnel-related regulations and systems, address grievances, assuage concerns, build consensus, and evaluate and execute JVAL.

Redress or Adverse Remarks?

JVAL would be a monumental shift in the way DOD, the Services, and the joint force historically have handled personnel. While instituting the cross-Service JVAL is not without its challenges, it is within the capability and capacity of DOD. The incentives to make the shift to JVAL are real. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter recently acknowledged at Harvard University that “we have a personnel management system that isn’t as modern as our forces deserve.”34 JVAL is that modern system, and DOD should implement it. Evaluations can be one more way to realize a more inclusive and accessible joint experience. JFQ

Notes

1 Calculation based on typical annual evaluation completed by a Servicemember with the addition of a one-third multiple to include infrequent evaluations related to promotion, special evaluations, separation, transfer, and relief of superior.

2 Office of the Under Secretary for Personnel and Readiness, “About,” available at <http://prhome.defense.gov/About.aspx>; Department of Defense (DOD), “DOD Personnel, Workforce, Reports & Publications,” available at <www.dmdc.osd.mil/appj/dwp/dwp_reports.jsp>.

3 The Army conducted the most recent evaluation reform and update to the DA Form 67-10 series in 2014 after 17 years using the previous DA Form 67-9 series.

4 For the purposes of this article, DOD is synonymous with the Office of the Secretary of Defense and military-civilian leadership. Additionally, the Services differ in the number and title for their respective evaluators. Therefore, rater, rating official, and reviewing official will be used to designate the evaluator.

5 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Additional Steps Are Needed to Strengthen DOD’s Oversight of Ethics and Professionalism Issues, GAO-15-711 (Washington, DC: GAO, September 2015), available at <www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-711 GAO-15-711>.

6 Adam Clemens and Shannon Phillips, The Fitness Report System for Marine Officers: Prior Research (Washington, DC: Center for Naval Analyses [CNA], November 2011); Adam Clemens et al., An Evaluation of the Fitness Report System for Marine Officers (Washington, DC: CNA, July 2012).

7 Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Force 2020 (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, September 10, 2012), 16, available at <http://dtic.mil/doctrine/concepts/ccjo_jointforce2020.pdf>.

8 National Military Strategy of the United States 2015 (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, June 2015), 13, available at <www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Publications/2015_National_Military_Strategy.pdf>.

9 Respectively, AF Form 707, NAVPERS 1610/2, and NAVMC 10835.

10 Respectively, DA Forms 67-10-1, 67-10-2, and 67-10-3.

11 The Navy plans to unveil a Web-based version of its evaluation writing software, eNAVFIT, in a few years.

12 Department of the Navy Marine Corps Order P1610.7F Ch 2, Performance Evaluation System (Washington, DC: Headquarters United States Marine Corps, November 19, 2010), 2, available at <www.hqmc.marines.mil/Portals/133/Docs/MCO%20P1610_7F%20W%20CH%201-2.pdf>.

13 Department of the Army Pamphlet 600–3, Commissioned Officer Professional Development and Career Management (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, December 3, 2014), 5, available at <www.apd.army.mil/pdffiles/p600_3.pdf>.

14 Ibid.

15 The Navy FITREP only has one rater, the reporting senior, unless it is a concurrent report.

16 This approach is borrowed from the Army. See Department of the Army Pamphlet 600–3, 11. Other Services have a similar construct. For example, the Navy breaks its officers into restricted line, unrestricted line, and staff categories.

17 The Yes/No portion for the Army takes place during the counseling phase. For the Navy and Marines, 0 and H refer to a non-observed trait, respectively.

18 See NAVMC 10835 (Marines) and AF Form 707 (Air Force).

19 Unlike the other three Services, the Navy’s FITREP only has one comments section, which is to be completed by the ratee for review by the rater. On the other hand, the Air Force has one more comments section than the Navy. This second comments section is reserved for an additional rater’s commentary.

20 Noted in internal presentation by U.S. Total Army Personnel Command (now Human Resources Command) to the Army G1 entitled Officer Evaluation Reporting System. For the Marines, see CNA, The Fitness Report System for Marine Officers: Prior Research and An Evaluation of the Fitness Report System for Marine Officers.

21 Officer and Enlisted Evaluation Systems (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Air Force, January 2, 2013), 49, available at <http://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2406/afi36-2406.pdf>.

22 Department of the Army Pamphlet 600–3, 10.

23 Ibid.

24 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, “Transition Assistance Program,” available at <http://benefits.va.gov/VOW/tap.asp>.

25 DOD, “Force of the Future [FotF],” available at <www.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/2015/0315_force-of-the-future/documents/FotF_Fact_Sheet_-_FINAL_11.18.pdf>. For 2016 FotF initiatives, see Cheryl Pellerin, “Carter Unveils Next Wave of Force of the Future Initiatives,” DOD News, June 9, 2016, available at <www.defense.gov/News-Article-View/Article/795625/carter-unveils-next-wave-of-force-of-the-future-initiatives>.

26 Department of the Navy, “Talent Management,” available at <www.secnav.navy.mil/innovation/Documents/2015/05/TalentManagementInitiatives.pdf>.

27 Once initiated, FotF did face significant congressional scrutiny as Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Brad Carson was replaced by Peter Levine after 1 year. See Jory Heckman, “Leading Defense Adviser Tapped to Be New Personnel Chief,” Federal News Radio, March 31, 2016, available at <http://federalnewsradio.com/people/2016/03/leading-defense-adviser-tapped-to-be-new-military-personnel-chief/>.

28 Eric Yoder, “Defense Department Begins New Employee Performance Rating System,” Washington Post, April 1, 2016, available at <www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/wp/2016/04/01/defense-department-begins-new-employee-performance-rating-system/>.

29 U.S. Code 10, § 5013 with regard to the roles and responsibilities of the Secretary of the Navy.

30 Department of the Navy, General Regulations, Chapter 11, Section 3, Article 1129, Records of Fitness, available at <https://doni.daps.dla.mil/US%20Navy%20Regulations/Chapter%2011%20-%20General%20Regulations.pdf>.

31 U.S. Code 10, §§ 131, 136, and 10201.

32 U.S. Code 10, § 153.

33 Mirroring Title 10 roles and responsibilities, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs would be the most likely candidate.

34 DOD, “News Transcript: Discussion with Secretary Carter at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum, Harvard Institute of Politics, Cambridge, Massachusetts,” December 1, 2015, available at <www.defense.gov/News/News-Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/632040/discussion-with-secretary-carter-at-the-john-f-kennedy-jr-forum-harvard-institu>.